Auto Emotion: Autobiography, Emotion and Self-Fashioning is the most ambitious and compelling group show seen at the Power Plant in recent memory, a belated showcase of what director Gregory Burke and curator Helena Reckitt–hired in 2005 and 2006, respectively–are capable of doing. The works on display all strike a delicate balance between conceptual rigour and messy affects, impulses and desires. They dramatize the mechanisms by which emotion, rather than simply occurring spontaneously or naturally, is produced, packaged and performed. The show revitalizes autobiographical performance-based practice by thinking through the seemingly transparent, raw and “real” emotional immediacy of much work in this field. With video in generally being the presentation medium of choice for the vast majority of the 14 participating artists, it is also gratifying to see old-fashioned single-channel video given such a place of prominence.

However, with this many artists, it is inevitable that some will not quite fit in. There is something too clean and detached about Rodney Graham and Rafael Lozano-Hammer’s practices to fit in with the hysterics and deconstructions thereof on display here, while Johannes Wohnseifer’s enigmatic, mechanical painting and video seem even more out of place. There are many strong individual pieces, such as the sprawling excerpts from Sophie Calle’s marvellous Exqubsite Pain (2000)–the centrepiece of the show, but discussed far too often elsewhere to comment on here–and Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay’s Lyric (2004), an exhaustive, sung catalogue emphasizing the numbing repetitiveness and redundancy of popular song lyrics. Nikki S. Lee’s photographic series, Parts (2003), meanwhile, succinctly and sweetly downs romantic love’s sentimentality in one fell swoop.

The most forceful work in the exhibition is Christian Jankowski’s Angels of Revenge (2006). Attending a horror convention’s costume competition in Chicago, Jankowski asked people how they were most wronged in life and how they would wish to avenge themselves against the person responsible. Jankowski shows that the desire for unvarnished (and uncensored) emotional truth and authenticity is still alive and well, especially because describing one’s brutal, homicidal desires continues to be considered in bad taste and taboo. I first viewed this work exactly one month after the Virginia Tech massacre, and Seung-hui Cho’s ridiculous Web-posted rantings and ravings were an inescapable touchstone for my experience of Jankowski’s work. (It is tempting to suggest that YouTube and its ilk are responsible for the resurgence in art of technically rudimentary, confessional and straight-to-camera videos that are–usually unintentionally-reminiscent of 70s video art.) Cho incoherently expressed an extreme mutation of the class envy that the American dream depends upon, while Jankowski parades the perversely capitalist eye-for-an-eye credo of an American culture trapped in a vortex of violence. In Jankowski’s video, empathy for his wronged subjects is all but eviscerated thanks to their excessive, identity-obscuring outfits; also, their descriptions of the offences against them tend to pale in comparison to their much more visceral and titillating (if inarticulate) revenge fantasies. Detached, we feel only the unease of watching someone sincerely describe their feelings without irony or self-consciousness. Men and women of various ages march out of the darkness and towards the camera as they narrate what happened to them and what they will do to “you.” The “you” is very important here, because we behind the camera are the perpetrators; the angels approach us, and at the moment when they reach the camera, a flash and a slashing sound inform us that “we” have been annihilated. Mixing insult and injury to chilling effect, whether detailing belt-sander castrations or obscene torture-rape, the confessions are giddily sadistic. Jankowski’s socially collaborative nihilism crystallizes one of the show’s strongest themes: the persistent complexities of performing social deviance.

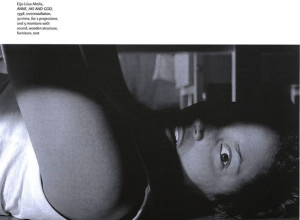

In Eija-Liisa Ahtila’s The Present (2001), a series of short public-service announcements urge viewers to “give yourself a present–forgive yourself.” Each is an impeccably shot and structured confession of sorts, wherein a woman performs a deviant compulsion while simultaneously analyzing her actions–“this is what I do”–and herself. For example, in The Bridge, a phobic woman must cross a bridge on hands and knees; she expounds on her good genes and testifies, “I can’t look in the mirror because who would I see? I realized that I looked mad. That that’s where the madness is” Swinging Curtains features a hospitalized woman confusing her caregivers for bloodthirsty intruders as she explains her elaborately designed emergency system for hiding under the bed when they come to murder her. Ahtila’s films essentially blow up women’s psychoses to epic proportions, forging a highly “professional” 35mm cinematic take on neuroses that are usually swept under the rug, making female deviance spectacular and formidable.

A couple of the more comic pieces in the show have the bare-bones single-channel video form most common for performance documentation; both are, interestingly enough, about the art world. Marina Abramovic ironizes the tropes of the endurance body art that she herself pioneered with The Onion (1996), wherein she voraciously devours an entire softball-sized bulb–skin and all–gazing heavenwards and glowing with an artificial light befitting a Fassbinder heroine. As she excretes more and more tears, moaning in agony with her chin covered in drool and chunks, a looping soundtrack of her voice drones on and on about her romantic and self-image woes, and her rough life as an icon. “I’m tired of being ashamed of my nose being too big, my ass being too large … I’m tired of changing planes so often.” Her instinctual onion-tears mock the pretense of self-pitying emotional tears.

While Ahtila and Abramovic both perform deviance, Andrea Fraser cuttingly critiques how such deviance is bought and sold in the art market in Official Welcome (2001). As Fraser gradually strips off her clothes while addressing an audience from her podium, her identity constantly shifts–in voice, in gesture, in rhetoric–between different (unnamed) art-world figures whom she quotes verbatim, alternating between toadying professionals (the introducers) and the artists eager to be “so right, so now” (the speakers). She presents an art market where grotesque and difficult have become marketing buzzwords, where “sex and excrement” are shorthand for honesty, and boundary-challenging experiences are bought and sold. She ruthlessly debunks how artists are positioned as “better than us,” ubermenschen permitted to “live our fantasies” on our behalf, whether of the victimized, abject woman or the foul-mouthed male genius who can’t suppress a disdainful laugh when he declares, “I used to think I could change the world” Fraser’s project embodies Auto Emotion’s renewal of the genre precisely by putting these affective aesthetic strategies under the gaze of a piercing intellect.