Due to the strange scale of his installations, Kai Schiemenz’s work occupies an ambiguous space between traditional media categories. Their playful and unlikely compositions within the gallery context make them appear to be architectural working models that have spontaneously expanded to enable human use. In fact, they are planned and composed in miniature form, and are built directly from test models through trial and error. This unpredictable quality gives Schiemenz’s work an improvised, experimental aura and a raw energy. And while in size and placement they maintain their autonomy as sculptural objects, these spaces are built for public interaction.

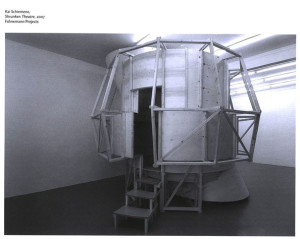

In Shrunken Theatre (2007), a torqued drum shape seems barely controlled by its exterior skeleton. Built precisely to the scale of the gallery, right up to the ceiling, it seems about to burst from the room. A series of elliptical sections overlap to comprise an irregular volume. The sliced and shifted sections result in horizontal ledges on the interior that act like benches. This is characteristic of a number of Schiemenz’s installations: concentric forms are dynamically manipulated in a way that creates precarious seating around a void, and a kind of constricted communal forum results. His constructions over the past three years have centred on variations of stages, theatres, planetariums, arenas and stadiums. In this respect, his work shares similar concerns and methods to the installations of Toronto artist Adrian Blackwell. But in Schiemenz’s work, there is conscious resizing of the typologies of mass public space to more intimate terms, and therefore from the scale of the crowd to that of the individual.

The modulation of scale is central to the odd psychological and behavioural effects provoked by the artist’s constructions. In Shrunken Theatre, a small entranceway allows access into a small viewing space. If there are already people inside, one is immediately self-conscious, and searches for a place to sit on one of the protruding shelves while trying not to block the video projection. Projected onto a wall area is a double-frame image of a heavy-set man in a white tutu, dancing with awkward flourishes in what looks like a school gym. The scene is filmed from two separate corners of the performance space and the two films are projected at once, so we see the man repeat the same absurd actions from two simultaneous points of view. The emphasis on spatial choreography and the distinction between viewpoints finds an echo in the way the viewer finds him- or herself interacting with the installation.

Schiemenz’s contorted architecture fosters exploration by the viewer/participant, but it does so in order to destabilize traditional concepts of democratic space. In contrast to the notion that public space can be conceived as a harmonious and homogenous whole, as discussed, for example, by the philosopher Jurgen Habermas, these installations can be better understood in relation to a democratic space of diversity, where parallel yet conflicting relationships are enacted. This idea of plurality in relation to public space is articulated by Chantal Mouffe as an “agonistic public sphere.” The unstable and shifting forms of Schiemenz’ installations do not intend or pretend to facilitate “open” debate, but allow spatial hierarchy, separation and clear articulations of outside and inside.

The installation Untitled (Stadium) (2005) at the Badischer Kunstverein in Karlsruhe consisted of a number of non-aligned elliptical rings that formed a series of ledges for seating inside and outside the towering structure. A marathon night of lectures, talks and screenings took place in and around this installation, and audience members were free to sit wherever they liked. This vision of public space is in contrast to mere representational transparency, such as that imagined by Norman Foster in his glass cupola for the Reichstag (the German parliament). The theme for the event at Untitled (Stadium) was “the production of world-models,” and a related publication further developed these ideas. The concept of the model is fundamental to Schiemenz’s method: for him, it enacts a notion of shared consciousness as a process of perennial reconstruction.

Schiemenz work continually considers the position of the viewer in order to frame the process of observation and awareness. In Communal Cinema within the Rings of Splendour (2006), a circular viewing screen is tilted at an oblique angle to reveal seating rings, in effect displaying the audience to the gallery visitor approaching the work. A further series of canted, circular space-frames helps to animate the work’s multidimensional displacement of space.

For the group exhibition Ideal City–Invisible Cities (2006) in Zamosc, Poland, Schiemenz built a tower construction that allowed visitors to see both the historically protected and obsolete old centre, planned and built as an ideal city in the 16th–century, and the surrounding suburban area, where the day-to-day functioning of urban life takes place. The title of this work, Endeavour’s Watchtower for the Fourth International indicates Schiemenz’ concern with ideas of ideological failure. Endeavour was one of the ships with which James Cook sailed to the Hawaiian Islands, where he was slain by the natives. Referring to this story of cultural conflict, the installation addresses the problems inherent in cultural projection. In homage to Vladimir Tatlin’s proposed Monument to the Third International (1919-20), the structure employs a twisted, tilting stair construction. The overt reference to Russian Constructivism evokes failed idealism, exposing a lost moment of history when art and technology were integrated with social purpose.

Perhaps the collision of systems and viewpoints and the contemplation of ideological collapse became important to Schiemenz when he was a student in East Berlin during the fall of the Wall and the subsequent abrupt transition between political regimes. His work emerges out of a particular scene in Berlin, prominent since the late 90s, which focuses specifically on spatial politics. This concentrated energy has produced many sophisticated publications, lecture series, film cycles, even fashion shows and concerts, as well as installations and exhibitions. In some ways, Schiemenz’s work is a critique of and reaction to the abundance of forums for “democratic debate” that fail to reveal structural hierarchies. This locates it in a continuum of art that looks at social structures, including, especially in the German context, the Social Sculptures of Joseph Beuys, who considered art a revolutionary “stimulant” to transform everyday life. Schiemenz’s installations combine sculptural delight with a realistic view of collective engagement that emphasizes individual responsibility and personal diversity, not an idealized and inhuman fake-flattening of hierarchies.