Twenty-five years later, many of the artists featured in the inaugural issue of C Magazine have proven they have staying power. This group includes Rae Johnson, whose role as a founder of the ChromaZone collective and exhibitions at the Carmen Lamanna Gallery had established her place in Toronto’s art mythology by 1983. She was, and endures as, it less conspicuously, a revered queen bee of a Toronto scene that was abuzz during the flamboyant, heated-up 80s.

Rae Johnson’s pedigree notwithstanding, there are long gaps between exhibitions–and bodies of work we have not seen. In spite of obstacles, she continued to make work to meet challenges she posed for herself and for her audience, arriving at a virtuosity that could only be attained through millions of brush strokes and trial and error. Her new work highlights aspirations that took time to fulfill.

One consistency amongst Johnson’s works is a negotiation with Modernism. Adherence to the strictures of a reductive and essentialist canon offered insufficient reason to hold in check what the artist calls “the need to make images about life around me as I saw it.” A second, related consistency is an interest in the power of images to convey archetypes; while a third is a wish to make paintings that honour her suspicions about our existence. In her close study of the visual world, Johnson noted the dissonance between how things appear–as solid, inherently existent objects apart from other objects in space–and how things might be. “Reading about the theory of relativity and particle physics made me think about the immateriality of our experience.” This concern drove work that resists the objectification of the body and of other phenomena.

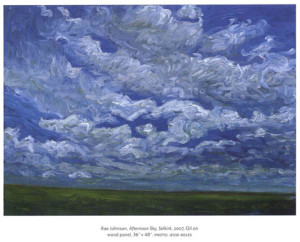

The inadequacy of tracking an artist’s work through reproductions was apparent to me when I came across a 2007 Rae Johnson painting tucked into a nook at Patti Petro’s summer show. To guide the eye, effect immersion and provoke emotion, Johnson’s painting employed particular scale and surface qualities that JPEGs fail to convey.

The arresting, mesmerizing and haunting painting was touched off by a late afternoon sky over Selkirk, Manitoba. Along a sloping horizon, reddish streaks divide a narrow wedge of green from sky blues, across which pushy brush strokes herd pale clusters flecked with glints of salmon pink. Snarled skeins on the left unravel into a spill of springy curls uncoiling upwards. In the lower right, dashes and smudges tweak a sense of reflections in standing water, a patch of visual density that braces up the horizon’s lopsided tilt.

A vertical spectrum of blue shades stepping from aqua through warmer shades blends at the zenith and looms over the band of grassy hues to stir a reflexive recognition of ‘landscape.’ However, loose brush play works against the paint tendrils, giving way to illusions of objects in space and resisting a David Milne-ish command over surface tension. The dialectic between surface and space is as moot as the picture’s reference to a site. Formal and representational attributes are given respectful but cursory attention, serving instead to impart a sense of how it feels to witness the scene firsthand. As Johnson puts it, “I don’t like the term landscape, because it suggests I am painting objects, when I am trying to convey the experience of our spiritual connection to our world through nature…. I am not interested in depicting the world as we see it, but as how we internalize and experience it.”

This nature study serves the same objective as Johnson’s renderings of archetypes, interiors, figures and media re-imaginations: to foster experience of “emotional content … like listening to music.” She admits that her work has not always been easy. In the early 80s, Johnson’s painting was, for me, hair-raising; in her words, it was striking “fear and loathing in our civilized composure. Painting as threat.”

A closer look at the Selkirk painting is still hair-raising, but less confrontational. Nevertheless, a Rae Johnson painting with manners is not Pollyanna-ish. Congested brush strokes in rough verticals and zigzags smear and gnaw into airy, calligraphic curves, a ghost hand groping for its way and bringing to mind Artur Schnabel’s phrase “from inwardness to lucidity.”

Johnson describes her process as one of ranging around the countryside until seized up by a moment of wonder, a “whoosh” Later, a digital-camera “thumbnail” serves as a mnemonic aid to initiate a painting in which she recovers the experience in order to foster it in others. The boundary between artist and viewer dissolves as world views conflate onto the fused horizon of the painting’s visual field. In the past, Johnson employed figurative distortions to indicate an elastic space-time; now she uses empathy to suggest a “seamless oneness” that pixels cannot record. She uses terms like “vibration” and “energy,” then gives up: “It’s impossible to put into words” So she paints, joining a lineage of artists whose work may be associated with aesthetic schools, but whose preoccupations are unapologetically transcendental.

The initial association stirred by the Selkirk painting was of adapting to glare, squinting and blinking at the sight of a homecoming sky overloaded with emotion and seen through the eyes of a mythic Persephone newly released from Hades. For me, the painting roused memories of driving west, making that sudden exit from inhospitable blackfly-infested forest, into a vast, open, windswept clearing. Although rooted in nature study, the painting generates overtones of relief and renewal.

I wonder if this painting signals that Johnson is emerging from immersion in the dark side, a preoccupation explicit in past work. She has described her paintings in terms of a duality of the seen and unseen, “the monde concrete we bump into and the unknowable dimensions of thought,” and as “uneasy fragments existing between objective experience and subjective perception … between conventional representation and the boundaries of the invisible” I wondered if her close “observations of the cycles of light and darkness” had effected a reconciliation of opposites. The artist’s response:

“It was a conscious decision. I decided that I only wanted to make things that people could look at that were–this is going to sound stupid, but–beautiful. And I don’t mean superficially pretty beautiful. I wanted to bring the sublime into people’s experience. I did my 9/11 airplanes and I just didn’t want to go to dark. I realized that my painting is another manifestation of putting energy out into the world. In trying to be responsible about the energy that I am putting out, I’m not going to put out more brutality.”

Rae Johnson utilizes pictorial conventions to infuse the merged horizons of painter and art lover with just enough of a consensus to strike up a relationship. The emotions aroused by the fierce resistances she presented in past works sometimes were uncomfortable; she now marshalls positive affect to serve her objectives.

As Flint Schier puts it in his comments on Wollheim, the kind of concern that Johnson has for her viewer–painting for the eyes of others and assuming ever more responsibility for the experience that she offers–“distinguishes mature art, or art per se, from the dream-work of children, fantasists, and dabblers who work simply to please themselves without imagining how their work would look from the perspective of a suitably disinterested, informed, sophisticated and imaginative spectator … a grasp of the full reality of other perspectives on one’s own work.”